Off-Broadway Cast, 1967 (RCA/DRG)

Off-Broadway Cast, 1967 (RCA/DRG)  (3 / 5) While this production did not achieve great success onstage, it did yield a cast album to be reckoned with. Most important, this is the only complete recording of one of the longest running musicals by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart; the original 1941 production opened before cast albums became a popular commodity. The score contains some of the team’s catchiest up-tempo numbers (“Ev’rything I’ve Got,” “Jupiter Forbid”) and loveliest ballads (“Wait Till You See Her,” “Nobody’s Heart,” “Careless Rhapsody”), all performed with gusto. Bob Dishy is very suitable as Sapiens, the reluctant groom to the Amazon Queen Hippolyta, whose numbers are sensationally belted out by Jackie Alloway. Meanwhile, the songs of the secondary romantic couple are beautifully delivered by Sheila Sullivan and Robert R. Kaye. — Jeffrey Dunn

(3 / 5) While this production did not achieve great success onstage, it did yield a cast album to be reckoned with. Most important, this is the only complete recording of one of the longest running musicals by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart; the original 1941 production opened before cast albums became a popular commodity. The score contains some of the team’s catchiest up-tempo numbers (“Ev’rything I’ve Got,” “Jupiter Forbid”) and loveliest ballads (“Wait Till You See Her,” “Nobody’s Heart,” “Careless Rhapsody”), all performed with gusto. Bob Dishy is very suitable as Sapiens, the reluctant groom to the Amazon Queen Hippolyta, whose numbers are sensationally belted out by Jackie Alloway. Meanwhile, the songs of the secondary romantic couple are beautifully delivered by Sheila Sullivan and Robert R. Kaye. — Jeffrey Dunn

Category Archives: A-C

By Jeeves

London Cast, 1996 (Polydor)

London Cast, 1996 (Polydor)  (3 / 5) Andrew Lloyd Webber and Alan Ayckbourn cleverly reworked their 1975 flop ]eeves into this chamber-size musical chronicling the misadventures of the hapless, rich-and-spoiled-but-lovable Bertie Wooster and his invaluable manservant. In size and style, it’s not that different from the musical comedies that the characters’ creator, P. G. Wodehouse, wrote with Guy Bolton and Jerome Kern. Lloyd Webber, after many years of creating supersized neo-operettas with awful lyrics, downscaled his ambitions and found his most sympathetic wordsmith yet; the distinguished playwright Ayckbourn turns out to be a deft lyrical craftsman with a gift for light verse. The modestly orchestrated songs are slight but ingratiating, and this London cast recording sets them up quite brilliantly with a running commentary by Jeeves and Wooster that untangles the convoluted plot with precision and aplomb. Malcolm Sinclair is an ideal gentleman’s gentleman, Steven Pacey a dexterous Wooster. Unfortunately, Lucy Tregear as Honoria Glossop and Cathy Sara as Stiffy Byng grate their way through such good songs as “Half a Moment” and “That Was Nearly Us.” Also, pleasant though the proceedings generally are, they’re a little forced; you can almost hear the creative team in the sound booth, yelling “More charm! More charm!” — Marc Miller

(3 / 5) Andrew Lloyd Webber and Alan Ayckbourn cleverly reworked their 1975 flop ]eeves into this chamber-size musical chronicling the misadventures of the hapless, rich-and-spoiled-but-lovable Bertie Wooster and his invaluable manservant. In size and style, it’s not that different from the musical comedies that the characters’ creator, P. G. Wodehouse, wrote with Guy Bolton and Jerome Kern. Lloyd Webber, after many years of creating supersized neo-operettas with awful lyrics, downscaled his ambitions and found his most sympathetic wordsmith yet; the distinguished playwright Ayckbourn turns out to be a deft lyrical craftsman with a gift for light verse. The modestly orchestrated songs are slight but ingratiating, and this London cast recording sets them up quite brilliantly with a running commentary by Jeeves and Wooster that untangles the convoluted plot with precision and aplomb. Malcolm Sinclair is an ideal gentleman’s gentleman, Steven Pacey a dexterous Wooster. Unfortunately, Lucy Tregear as Honoria Glossop and Cathy Sara as Stiffy Byng grate their way through such good songs as “Half a Moment” and “That Was Nearly Us.” Also, pleasant though the proceedings generally are, they’re a little forced; you can almost hear the creative team in the sound booth, yelling “More charm! More charm!” — Marc Miller

American Premiere Recording, 2001 (Decca)

American Premiere Recording, 2001 (Decca)  (2 / 5) In New York, By ]eeves honorably attempted to inject some Wodehousian fun into the very tense, post-9/11 Broadway atmosphere. The show struggled for about two months, shuttering the night before New Year’s Eve. The selling points of this cast album are mainly on the distaff side. Donna Lynne Champlin’s Honoria Glossop is more vocally assured than Lucy Tregear’s on the London recording, but Champlin, too, goes overboard, hamming through “That Was Nearly Us.” Emily Loesser’s Stiffy Bing has it all over Cathy Sara’s turn in London. Becky Watson’s Madeline Bassett is charming in “When Love Arrives” and “It’s a Pig!” As Bertie Wooster and Bingo Little, respectively,John Scherer and DonStephenson sing well. But the CD is poorly packaged, with only a few thumbnail photos and no lyrics or plot synopsis. And while the London cast album has all that smart verbal interplay between Jeeves and Wooster, this edition gives us just the songs. Martin Jarvis’ Jeeves is on hand for a few tracks and then slips discreetly away — very Jeevesian of him but, plot-wise, it leaves us hanging. — M.M.

(2 / 5) In New York, By ]eeves honorably attempted to inject some Wodehousian fun into the very tense, post-9/11 Broadway atmosphere. The show struggled for about two months, shuttering the night before New Year’s Eve. The selling points of this cast album are mainly on the distaff side. Donna Lynne Champlin’s Honoria Glossop is more vocally assured than Lucy Tregear’s on the London recording, but Champlin, too, goes overboard, hamming through “That Was Nearly Us.” Emily Loesser’s Stiffy Bing has it all over Cathy Sara’s turn in London. Becky Watson’s Madeline Bassett is charming in “When Love Arrives” and “It’s a Pig!” As Bertie Wooster and Bingo Little, respectively,John Scherer and DonStephenson sing well. But the CD is poorly packaged, with only a few thumbnail photos and no lyrics or plot synopsis. And while the London cast album has all that smart verbal interplay between Jeeves and Wooster, this edition gives us just the songs. Martin Jarvis’ Jeeves is on hand for a few tracks and then slips discreetly away — very Jeevesian of him but, plot-wise, it leaves us hanging. — M.M.

Bye Bye Birdie

Original Broadway Cast, 1960 (Columbia/Sony)

Original Broadway Cast, 1960 (Columbia/Sony)  (5 / 5) Here is pure pleasure. Bye Bye Birdie, with a book by Michael Stewart, managed to satirize the Elvis Presley craze, racial prejudice, the generation gap, the Shriners, and so on, while retaining a thoroughly plausible air of innocence. The cast is ideal: Dick Van Dyke has an easy charm and faultless timing as pop songwriter Albert, who faces disaster when his meal ticket, the hip-swiveling teen idol Conrad Birdie (Dick Gautier), is drafted. Chita Rivera is sensational as Albert’s exasperated assistant/girlfriend, Rosie. As Kim, the winsome teenager chosen to kiss Birdie in a televised farewell, Susan Watson shows why she was a top Broadway ingenue in her day. Paul Lynde, as Kim’s harried dad, is the least likely husband and father imaginable but is hilarious nonetheless. Birdie was the making of composer Charles Strouse and lyricist Lee Adams, for good reason. This is the rare Broadway score in which the comedy numbers retain their humor. Among the comedic highlights are “The Telephone Hour,” in which a horde of teenagers gossip about the budding romance in their midst; “Healthy, Normal American Boy,” in which Albert and Rosie feed outrageous lies about Conrad to the press; “Hymn for a Sunday Evening,” a paean to Ed Sullivan’s insanely popular TV variety show, complete with Lynde’s priceless reading of the line, “Ed, I love you!”; “Kids,” the parents’ cri-de-coeur; and “Spanish Rose,” in which Rivera is a campy delight (“I’Il be more Español than Abbe Lane!”). Add a couple of songs that became standards (“Put On a Happy Face,” “A Lot of Livin’ to Do”) and what more do you need? Robert Ginzler’s orchestrations keep the tone light and bright throughout. This recording is essential to any Broadway collection. (A CD bonus track features Strouse discussing the show and singing “Put On a Happy Face.”) — David Barbour

(5 / 5) Here is pure pleasure. Bye Bye Birdie, with a book by Michael Stewart, managed to satirize the Elvis Presley craze, racial prejudice, the generation gap, the Shriners, and so on, while retaining a thoroughly plausible air of innocence. The cast is ideal: Dick Van Dyke has an easy charm and faultless timing as pop songwriter Albert, who faces disaster when his meal ticket, the hip-swiveling teen idol Conrad Birdie (Dick Gautier), is drafted. Chita Rivera is sensational as Albert’s exasperated assistant/girlfriend, Rosie. As Kim, the winsome teenager chosen to kiss Birdie in a televised farewell, Susan Watson shows why she was a top Broadway ingenue in her day. Paul Lynde, as Kim’s harried dad, is the least likely husband and father imaginable but is hilarious nonetheless. Birdie was the making of composer Charles Strouse and lyricist Lee Adams, for good reason. This is the rare Broadway score in which the comedy numbers retain their humor. Among the comedic highlights are “The Telephone Hour,” in which a horde of teenagers gossip about the budding romance in their midst; “Healthy, Normal American Boy,” in which Albert and Rosie feed outrageous lies about Conrad to the press; “Hymn for a Sunday Evening,” a paean to Ed Sullivan’s insanely popular TV variety show, complete with Lynde’s priceless reading of the line, “Ed, I love you!”; “Kids,” the parents’ cri-de-coeur; and “Spanish Rose,” in which Rivera is a campy delight (“I’Il be more Español than Abbe Lane!”). Add a couple of songs that became standards (“Put On a Happy Face,” “A Lot of Livin’ to Do”) and what more do you need? Robert Ginzler’s orchestrations keep the tone light and bright throughout. This recording is essential to any Broadway collection. (A CD bonus track features Strouse discussing the show and singing “Put On a Happy Face.”) — David Barbour

Original London Cast, 1961 (Philips/Decca) No stars; not recommended. This show did not thrive in the West End, and the cast recording is inferior to the Broadway album in almost every way. Rivera is still on hand, but Peter Marshall, as Albert, tends to overwhelm the numbers — although he does a nice job with “Baby, Talk to Me.” Sylvia Tysick’s chirping as Kim is a trial, and Robert Nichols’ straightforward approach (emphasis on the “straight”) to Mr. MacAfee results in no laughs whatever. Marty Wilde, a British pop star at the time, is a persuasive Birdie; but conductor Alyn Ainsworth’s slower tempi undermine the score’s humor and brio, especially in “The Telephone Hour,” which is further marred by the cast’s pitch problems and shaky American accents. — D.B.

Original London Cast, 1961 (Philips/Decca) No stars; not recommended. This show did not thrive in the West End, and the cast recording is inferior to the Broadway album in almost every way. Rivera is still on hand, but Peter Marshall, as Albert, tends to overwhelm the numbers — although he does a nice job with “Baby, Talk to Me.” Sylvia Tysick’s chirping as Kim is a trial, and Robert Nichols’ straightforward approach (emphasis on the “straight”) to Mr. MacAfee results in no laughs whatever. Marty Wilde, a British pop star at the time, is a persuasive Birdie; but conductor Alyn Ainsworth’s slower tempi undermine the score’s humor and brio, especially in “The Telephone Hour,” which is further marred by the cast’s pitch problems and shaky American accents. — D.B.

Film Soundtrack, 1963 (RCA)

Film Soundtrack, 1963 (RCA)  (1 / 5) Irving Brecher’s screenplay altered the show’s plot to the point of terminal silliness, adding such complications as a troupe of snooty Russian dancers and a super-effective pep pill. But Strouse and Adams did come up with a kicky new title tune, delivered with gusto by Ann-Margret’s Kim, played as a voluptuous teenager. Van Dyke is still charming and Lynde is still a riot, but a game Janet Leigh isn’t an acceptable substitute for Rivera; the role of Rosie has lost much of its humor along with the songs “An English Teacher,” “Normal American Boy,” and “Spanish Rose.” The soundtrack recording doesn’t replace the Broadway album, but it’s fun if you’re an Ann-Margret fan, and the most recent CD edition features three previously unreleased tracks. — D.B.

(1 / 5) Irving Brecher’s screenplay altered the show’s plot to the point of terminal silliness, adding such complications as a troupe of snooty Russian dancers and a super-effective pep pill. But Strouse and Adams did come up with a kicky new title tune, delivered with gusto by Ann-Margret’s Kim, played as a voluptuous teenager. Van Dyke is still charming and Lynde is still a riot, but a game Janet Leigh isn’t an acceptable substitute for Rivera; the role of Rosie has lost much of its humor along with the songs “An English Teacher,” “Normal American Boy,” and “Spanish Rose.” The soundtrack recording doesn’t replace the Broadway album, but it’s fun if you’re an Ann-Margret fan, and the most recent CD edition features three previously unreleased tracks. — D.B.

Television Film Soundtrack, 1995 (RCA Victor)

Television Film Soundtrack, 1995 (RCA Victor)  (1 / 5) The TV film that yielded this recording is more faithful to the Broadway production than was the 1963 big-screen version. The soundtrack recording benefits from the charmingly sung Kim of Chynna Phillips and the amusingly over-the-top Birdie of Marc Kudisch. George Wendt offers a refreshing take on Mr. MacAfee, but Jason Alexander as Albert pushes too hard for his laughs; 30 seconds into “Put On a Happy Face,” you’ll be yearning for Dick Van Dyke. Vanessa Williams is a vocally confident Rosie, yet her performance lacks fire; even outfitted with clever new lyrics, “Spanish Rose” isn’t really her thing. Two numbers have been added: “A Mother Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” sung by Tyne Daly as Albert’s castrating mom, makes an obvious point obviously; and “Let’s Settle Down,” a ballad for Williams, sounds jarringly like one of the singer’s pop hits. — D.B.

(1 / 5) The TV film that yielded this recording is more faithful to the Broadway production than was the 1963 big-screen version. The soundtrack recording benefits from the charmingly sung Kim of Chynna Phillips and the amusingly over-the-top Birdie of Marc Kudisch. George Wendt offers a refreshing take on Mr. MacAfee, but Jason Alexander as Albert pushes too hard for his laughs; 30 seconds into “Put On a Happy Face,” you’ll be yearning for Dick Van Dyke. Vanessa Williams is a vocally confident Rosie, yet her performance lacks fire; even outfitted with clever new lyrics, “Spanish Rose” isn’t really her thing. Two numbers have been added: “A Mother Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” sung by Tyne Daly as Albert’s castrating mom, makes an obvious point obviously; and “Let’s Settle Down,” a ballad for Williams, sounds jarringly like one of the singer’s pop hits. — D.B.

Brownstone

Studio Cast, 2002 (Original Cast Records)

Studio Cast, 2002 (Original Cast Records)  (3 / 5) Five city dwellers share a brownstone but only occasionally interact with one another in this show by Josh Rubins, Andrew Cadiff, and Peter Larson. Brownstone feels more like a song cycle than a full-blown musical, which may explain why it disappeared after two brief Off-Broadway runs in the mid-1980s. This studio album, recorded after a well-received revival at the Berkshire Theatre Festival, makes a strong case for the score. Liz Callaway is Claudia, who is getting over a recent breakup. Brian d’Arcy James is Howard, a struggling novelist, and Rebecca Luker is Mary, his wife, who wants their future to include children. Debbie Gravitte plays Joan, a high-powered lawyer with a boyfriend in Maine. Kevin Reed is Stuart, the new guy, eager to find excitement and romance in the big city. Song by song, there’s much to enjoy here. Highlights include the scene-setting “Someone’s Moving In”; “Fiction Writer,” in which Howard fantasizes grinding out a best-selling thriller; “Not Today,” Joan’s dream of another life; and the achingly beautiful “Since You Stayed Here,” in which Claudia reviews the changes in her life after her break with her lover. The problem with the show is cumulative: Practically nothing happens, and the single note of wistful longing mixed with ambivalence is stretched extremely thin. Then again, with a first-class cast and a range of material that runs from not bad to very, very good, there’s much to like here. Plus, there are nice orchestrations by Harold Wheeler throughout. — David Barbour

(3 / 5) Five city dwellers share a brownstone but only occasionally interact with one another in this show by Josh Rubins, Andrew Cadiff, and Peter Larson. Brownstone feels more like a song cycle than a full-blown musical, which may explain why it disappeared after two brief Off-Broadway runs in the mid-1980s. This studio album, recorded after a well-received revival at the Berkshire Theatre Festival, makes a strong case for the score. Liz Callaway is Claudia, who is getting over a recent breakup. Brian d’Arcy James is Howard, a struggling novelist, and Rebecca Luker is Mary, his wife, who wants their future to include children. Debbie Gravitte plays Joan, a high-powered lawyer with a boyfriend in Maine. Kevin Reed is Stuart, the new guy, eager to find excitement and romance in the big city. Song by song, there’s much to enjoy here. Highlights include the scene-setting “Someone’s Moving In”; “Fiction Writer,” in which Howard fantasizes grinding out a best-selling thriller; “Not Today,” Joan’s dream of another life; and the achingly beautiful “Since You Stayed Here,” in which Claudia reviews the changes in her life after her break with her lover. The problem with the show is cumulative: Practically nothing happens, and the single note of wistful longing mixed with ambivalence is stretched extremely thin. Then again, with a first-class cast and a range of material that runs from not bad to very, very good, there’s much to like here. Plus, there are nice orchestrations by Harold Wheeler throughout. — David Barbour

Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk

Original Broadway Cast, 1996 (RCA)

Original Broadway Cast, 1996 (RCA)  (4 / 5) The songs aren’t the main point of this brilliant revue, which uses dance to chart the history of black men in America. The hip, hip-hop survey stretches from the days of slavery, when people were brought to this country in chains, to the “freedom” of today, when hailing a taxi to certain neighborhoods is still a challenge. It makes cogent stops at cotton fields, factories, sound stages, and prisons. Savion Glover, the musical’s driving force, astounded audiences with his groundbreaking approach to tap dancing. He calls what he does “hitting” — and, in an endless series of lightning fast, bravura movements, he changed the face (the feet?) of an ever-adaptable art form. Considering that dance was the impetus for Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk, which was skillfully directed by George C. Wolfe, one might expect that the cast recording would suffer. But Glover and Wolfe knew that rhythm was the underpinning of the show, and the album features lots of recorded footwork. A rock contingent headed by pianist Zane Mark provides the metaphorical floor on which Glover and fellow dancers Baakari Wilder, Jimmy Tate, and Vincent Bingham do their forceful, fanciful stuff. The music is by Mark, Daryl Waters, and Ann Duquesnay. Reg E. Gaines contributed the book, which covers some fantastical and brutal territory, and some of the lyrics, which do the same. Jeffrey Wright speaks most of the narration, and Duquesnay, who boasts a great growl, sings most of the songs, some of the time hurling lyrics that she herself came up with. Accompanying the CD is a booklet in which each segment is helpfully described. When musical theater historians look back on the 1990s, they will agree that this innovative show was one of the decade’s true triumphs. — David Finkle

(4 / 5) The songs aren’t the main point of this brilliant revue, which uses dance to chart the history of black men in America. The hip, hip-hop survey stretches from the days of slavery, when people were brought to this country in chains, to the “freedom” of today, when hailing a taxi to certain neighborhoods is still a challenge. It makes cogent stops at cotton fields, factories, sound stages, and prisons. Savion Glover, the musical’s driving force, astounded audiences with his groundbreaking approach to tap dancing. He calls what he does “hitting” — and, in an endless series of lightning fast, bravura movements, he changed the face (the feet?) of an ever-adaptable art form. Considering that dance was the impetus for Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk, which was skillfully directed by George C. Wolfe, one might expect that the cast recording would suffer. But Glover and Wolfe knew that rhythm was the underpinning of the show, and the album features lots of recorded footwork. A rock contingent headed by pianist Zane Mark provides the metaphorical floor on which Glover and fellow dancers Baakari Wilder, Jimmy Tate, and Vincent Bingham do their forceful, fanciful stuff. The music is by Mark, Daryl Waters, and Ann Duquesnay. Reg E. Gaines contributed the book, which covers some fantastical and brutal territory, and some of the lyrics, which do the same. Jeffrey Wright speaks most of the narration, and Duquesnay, who boasts a great growl, sings most of the songs, some of the time hurling lyrics that she herself came up with. Accompanying the CD is a booklet in which each segment is helpfully described. When musical theater historians look back on the 1990s, they will agree that this innovative show was one of the decade’s true triumphs. — David Finkle

Bombay Dreams

Original London Cast, 2002 (Sony)

Original London Cast, 2002 (Sony)  (3 / 5) This is the world’s first pop-rock, English-Hindi-Punjabi stage musical — but it isn’t as exotic as it sounds. Andrew Lloyd Webber produced the show, “based on an idea” that he and Shekar Kapur devised, about a naif finding fame in the hyperactive Bombay film industry known as Bollywood. Like most Lloyd Webber shows, Bombay Dreams is big on spectacle (the saris! the fountains!) but short on logic; it exists mainly as a showcase for a popular young composer, in this case, A. R. Rahman, who has written the music for dozens of Bollywood films. Rahman is a real talent with a lively gift for melody and a wide palette of styles. The recording opens with quiet mystery: Chords waft in as chant-like singing creates an atmosphere of suspense, then you can practically hear the smoke clearing as the slums of Bombay (now called Mumbai) awaken. The pace picks up and a beguiling tune kicks in, along with Don Black’s leaden lyrics, as the ambitious hero Akaash (Raza Jaffrey) dreams of stardom: “Like an eagle was born to fly, ride across the open sky / I was born to be seen on a screen in Bollywood.” And then the show plows through the expected: good guys versus bad, concerned families, broad humor, splashy musical numbers. It all adds up to a boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl, eunuch-sings-about-love musical. With breathy voices given digital treatments a la Cher, the album has a trendy pop sound that’s impossible to resist. The lyrics of “Shakalaka Baby” are silly, yet the song is infectious and lots of fun. (Note: A revised version of Bombay Dreams, with a book adapted by Thomas Meehan and some new songs, opened on Broadway in 2004 and ran for eight months, but did not yield a cast recording.) — Robert Sandla

(3 / 5) This is the world’s first pop-rock, English-Hindi-Punjabi stage musical — but it isn’t as exotic as it sounds. Andrew Lloyd Webber produced the show, “based on an idea” that he and Shekar Kapur devised, about a naif finding fame in the hyperactive Bombay film industry known as Bollywood. Like most Lloyd Webber shows, Bombay Dreams is big on spectacle (the saris! the fountains!) but short on logic; it exists mainly as a showcase for a popular young composer, in this case, A. R. Rahman, who has written the music for dozens of Bollywood films. Rahman is a real talent with a lively gift for melody and a wide palette of styles. The recording opens with quiet mystery: Chords waft in as chant-like singing creates an atmosphere of suspense, then you can practically hear the smoke clearing as the slums of Bombay (now called Mumbai) awaken. The pace picks up and a beguiling tune kicks in, along with Don Black’s leaden lyrics, as the ambitious hero Akaash (Raza Jaffrey) dreams of stardom: “Like an eagle was born to fly, ride across the open sky / I was born to be seen on a screen in Bollywood.” And then the show plows through the expected: good guys versus bad, concerned families, broad humor, splashy musical numbers. It all adds up to a boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl, eunuch-sings-about-love musical. With breathy voices given digital treatments a la Cher, the album has a trendy pop sound that’s impossible to resist. The lyrics of “Shakalaka Baby” are silly, yet the song is infectious and lots of fun. (Note: A revised version of Bombay Dreams, with a book adapted by Thomas Meehan and some new songs, opened on Broadway in 2004 and ran for eight months, but did not yield a cast recording.) — Robert Sandla

The Boy From Oz

Original Australian Cast, 1998 (EMI)

Original Australian Cast, 1998 (EMI)  (3 / 5) Peter Allen wrote only one musical — the inane Legs Diamond, still prized by connoisseurs of flops — but his life story plays itself out in this glossy show. The Boy From Oz is a fast-paced biography and the first home-grown Australian musical theater hit. It traces Allen’s life from his tap dancing, piano-playing youth through his career as pop songwriter, showman, and celebrity gadabout. His meteoric rise to fame ended with his death from AIDS in 1992. The musical covers Allen’s work with Judy Garland, his marriage to Liza Minnelli, and, to no one’s surprise but his own, his belated realization that he was gay. Nick Enright’s flimsy book shoehorns Allen’s songs into dramatic contexts with varying success. “When I Get My Name in Lights” (from Legs Diamond) works well for the young Peter (Mathew Waters). Todd McKenney is charming and engaged as the adult Allen, with a reedy tenor that sails through the anthemic “I Still Call Australia Home.” Chrissie Amphlett makes an interesting Garland — she and McKenney have great rapport in “Only an Older Woman” — while Angela Toohey’s Liza is a dizzy whirlwind. Bits of the script heard on the recording, such as a news flash about the Stonewall Riots, give context to Allen’s growing self-knowledge. Although the album has an earnest, unpretentious feel, Allen’s original renditions of his songs are catchier than these, and no one can beat Olivia Newton-John’s version of “I Honestly Love You” for syrupy bathos. Still, this is a fun album, hokey but warm-hearted. — Robert Sandla

(3 / 5) Peter Allen wrote only one musical — the inane Legs Diamond, still prized by connoisseurs of flops — but his life story plays itself out in this glossy show. The Boy From Oz is a fast-paced biography and the first home-grown Australian musical theater hit. It traces Allen’s life from his tap dancing, piano-playing youth through his career as pop songwriter, showman, and celebrity gadabout. His meteoric rise to fame ended with his death from AIDS in 1992. The musical covers Allen’s work with Judy Garland, his marriage to Liza Minnelli, and, to no one’s surprise but his own, his belated realization that he was gay. Nick Enright’s flimsy book shoehorns Allen’s songs into dramatic contexts with varying success. “When I Get My Name in Lights” (from Legs Diamond) works well for the young Peter (Mathew Waters). Todd McKenney is charming and engaged as the adult Allen, with a reedy tenor that sails through the anthemic “I Still Call Australia Home.” Chrissie Amphlett makes an interesting Garland — she and McKenney have great rapport in “Only an Older Woman” — while Angela Toohey’s Liza is a dizzy whirlwind. Bits of the script heard on the recording, such as a news flash about the Stonewall Riots, give context to Allen’s growing self-knowledge. Although the album has an earnest, unpretentious feel, Allen’s original renditions of his songs are catchier than these, and no one can beat Olivia Newton-John’s version of “I Honestly Love You” for syrupy bathos. Still, this is a fun album, hokey but warm-hearted. — Robert Sandla

Original Broadway Cast, 2004 (Decca)

Original Broadway Cast, 2004 (Decca)  (3 / 5) The Broadway cast album of The Boy From Oz is like the Australian album on steroids: It boasts punchier orchestrations, stronger voices, and, most crucially, Hugh Jackman in the title role. All of this plus superior sound gives this recording lots of presence and oomph — just what Peter Allen was all about. Even the CD packaging is more luxurious, with crisp graphics, complete lyrics, and colorful production shots. The Broadway version retains the structure of the Australian original, but some songs have been assigned to different characters or scenes, and the show now opens with the ruminative “The Lives of Me.” None of this disguises the facts that the musical is insubstantial and Jackman was the sole reason for the Broadway production. His strong, flexible voice is full of energy, easy confidence, and star power. While his thrilling stage performance does not translate fully to the recording, he is still an engaging leading man; his “Bi-coastal” and “Everything Is New Again” shine with showbiz know-how. Isabel Keating’s Judy Garland is febrile and funny, delivered with a fine belt. Stephanie J. Block rises to the challenge of the dramatic range that the Liza character gets in this version; she seems to grow in her songs, climaxing with a frenetic “She Loves to Hear the Music.” Jarrod Emick does what he can with the treacly “I Honestly Love You,” and Beth Fowler, as Allen’s mother, is a quiet powerhouse in “Don’t Cry Out Loud.” Of the two recordings of the show, this is the one to get. — R.S.

(3 / 5) The Broadway cast album of The Boy From Oz is like the Australian album on steroids: It boasts punchier orchestrations, stronger voices, and, most crucially, Hugh Jackman in the title role. All of this plus superior sound gives this recording lots of presence and oomph — just what Peter Allen was all about. Even the CD packaging is more luxurious, with crisp graphics, complete lyrics, and colorful production shots. The Broadway version retains the structure of the Australian original, but some songs have been assigned to different characters or scenes, and the show now opens with the ruminative “The Lives of Me.” None of this disguises the facts that the musical is insubstantial and Jackman was the sole reason for the Broadway production. His strong, flexible voice is full of energy, easy confidence, and star power. While his thrilling stage performance does not translate fully to the recording, he is still an engaging leading man; his “Bi-coastal” and “Everything Is New Again” shine with showbiz know-how. Isabel Keating’s Judy Garland is febrile and funny, delivered with a fine belt. Stephanie J. Block rises to the challenge of the dramatic range that the Liza character gets in this version; she seems to grow in her songs, climaxing with a frenetic “She Loves to Hear the Music.” Jarrod Emick does what he can with the treacly “I Honestly Love You,” and Beth Fowler, as Allen’s mother, is a quiet powerhouse in “Don’t Cry Out Loud.” Of the two recordings of the show, this is the one to get. — R.S.

Bring Back Birdie

Original Broadway Cast, 1980 (Varèse Sarabande) No stars; not recommended. What were they thinking? Clearly unaware that Elvis had left the building, the creators of Bye Bye Birdie reunited in 1980 for this misbegotten sequel, which trashed everything that was charming about the original. The cast album proves that even Charles Strouse and Lee Adams are capable of writing a lousy score. In Michael Stewart’s barely coherent story line, Albert and Rose, happily married for 20 years, search for the vanished Birdie to have him appear on a Grammy Awards telecast. They wind up in Bent River Junction, Arizona, where an overweight Birdie is the mayor and Albert’s mother, Mae, is a bartender. Meanwhile, daughter Jenny takes up with the religious cult “The Sunnies,” and son Albert, Jr. joins a band called Filth (they perform on toilets). Presiding over the mishmash is Chita Rivera — who, amazingly, never condescends to the material. For her efforts, she gets the score’s two most pleasant items, “Twenty Happy Years” and “Well, I’m Not!” Donald O’Connor does what he can with several numbers that make Albert out to be a selfish dope. Other hard workers include Maurice Hines as a private eye and Maria Karnilova as Mae; she gets the 11-o’clock number, a pointless Charleston titled “I Love ‘Em All.” As Birdie, Elvis impersonator Marcel Forestieri is amusing in “You Can Never Go Back,” words that the show’s creators might have heeded. With this as an example of what can happen when you try to make lighting strike twice, how did Strouse ever get involved with Annie Warbucks as one of his subsequent projects? — David Barbour

Original Broadway Cast, 1980 (Varèse Sarabande) No stars; not recommended. What were they thinking? Clearly unaware that Elvis had left the building, the creators of Bye Bye Birdie reunited in 1980 for this misbegotten sequel, which trashed everything that was charming about the original. The cast album proves that even Charles Strouse and Lee Adams are capable of writing a lousy score. In Michael Stewart’s barely coherent story line, Albert and Rose, happily married for 20 years, search for the vanished Birdie to have him appear on a Grammy Awards telecast. They wind up in Bent River Junction, Arizona, where an overweight Birdie is the mayor and Albert’s mother, Mae, is a bartender. Meanwhile, daughter Jenny takes up with the religious cult “The Sunnies,” and son Albert, Jr. joins a band called Filth (they perform on toilets). Presiding over the mishmash is Chita Rivera — who, amazingly, never condescends to the material. For her efforts, she gets the score’s two most pleasant items, “Twenty Happy Years” and “Well, I’m Not!” Donald O’Connor does what he can with several numbers that make Albert out to be a selfish dope. Other hard workers include Maurice Hines as a private eye and Maria Karnilova as Mae; she gets the 11-o’clock number, a pointless Charleston titled “I Love ‘Em All.” As Birdie, Elvis impersonator Marcel Forestieri is amusing in “You Can Never Go Back,” words that the show’s creators might have heeded. With this as an example of what can happen when you try to make lighting strike twice, how did Strouse ever get involved with Annie Warbucks as one of his subsequent projects? — David Barbour

Brigadoon

Original Broadway Cast, 1947 (RCA)

Original Broadway Cast, 1947 (RCA)  (4 / 5) This is one of the most exciting cast albums of the pre-LP era. It was RCA’s first stab at Broadway, and although the mono sound is antique by today’s standards, it’s crisp for its era. The orchestra seems augmented for the recording, and Franz Allers’ conducting is rousing. David Brooks plays Tommy, a world-weary romantic who, with his cynical friend Jeff, stumbles upon a Scottish village that comes to life for only one day every 100 years. Tommy falls in love with the lass Fiona, played by Marion Bell. The two leads combine legitimate vocal training and a full-bodied Broadway sound with believable acting and unaffected diction, soaring through such magnificent Alan Jay Lerner-Frederick Loewe songs as “The Heather on the Hill” and “Almost Like Being in Love.” Lee Sullivan as Charlie Dalrymple delivers impeccable renditions of ”I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and the wistful ballad “Come to Me, Bend to Me.” Since these recordings were originally released as a 78-rpm set, the score is truncated, but the cuts were made so carefully that the album doesn’t sound incomplete — except for the excision of the character Meg Brockie’s wonderfully witty Act I number “The Love of My Life.” What we have here is a vibrant reading of highlights of a great score that has all the freshness of a new Broadway smash by two songwriters who went on to more than fulfill their promise. — Gerard Alessandrini

(4 / 5) This is one of the most exciting cast albums of the pre-LP era. It was RCA’s first stab at Broadway, and although the mono sound is antique by today’s standards, it’s crisp for its era. The orchestra seems augmented for the recording, and Franz Allers’ conducting is rousing. David Brooks plays Tommy, a world-weary romantic who, with his cynical friend Jeff, stumbles upon a Scottish village that comes to life for only one day every 100 years. Tommy falls in love with the lass Fiona, played by Marion Bell. The two leads combine legitimate vocal training and a full-bodied Broadway sound with believable acting and unaffected diction, soaring through such magnificent Alan Jay Lerner-Frederick Loewe songs as “The Heather on the Hill” and “Almost Like Being in Love.” Lee Sullivan as Charlie Dalrymple delivers impeccable renditions of ”I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and the wistful ballad “Come to Me, Bend to Me.” Since these recordings were originally released as a 78-rpm set, the score is truncated, but the cuts were made so carefully that the album doesn’t sound incomplete — except for the excision of the character Meg Brockie’s wonderfully witty Act I number “The Love of My Life.” What we have here is a vibrant reading of highlights of a great score that has all the freshness of a new Broadway smash by two songwriters who went on to more than fulfill their promise. — Gerard Alessandrini

Film Soundtrack, 1954 (MGM/Rhino-Turner)

Film Soundtrack, 1954 (MGM/Rhino-Turner)  (2 / 5) MGM’s screen version of Brigadoon was misguided in many ways. Lerner and Loewe’s great score is not well served here. The orchestrations sound transparent and timid, and the casting of Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse in what were rich singing roles in the Broadway show transformed them into dancing roles, causing some beautiful ballads to be discarded. Also cut were both of Meg Brockie’s songs, because they were considered too risqué for 1954 movie audiences. However, some of what remains is robustly performed. The dance music will entertain those who love “The MGM Musical Sound,” and if you’re a big Gene Kelly fan, you may enjoy Rhino’s expanded CD, which includes Kelly’s renditions of the cut songs “There But for You Go I” and “From This Day On.” Also included is another number that was excised from the film, “Come to Me, Bend to Me,” sweetly sung by John Gustafsen, who dubbed for Jimmie Thompson. But this isn’t Brigadoon as we all know and love it. — G.A.

(2 / 5) MGM’s screen version of Brigadoon was misguided in many ways. Lerner and Loewe’s great score is not well served here. The orchestrations sound transparent and timid, and the casting of Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse in what were rich singing roles in the Broadway show transformed them into dancing roles, causing some beautiful ballads to be discarded. Also cut were both of Meg Brockie’s songs, because they were considered too risqué for 1954 movie audiences. However, some of what remains is robustly performed. The dance music will entertain those who love “The MGM Musical Sound,” and if you’re a big Gene Kelly fan, you may enjoy Rhino’s expanded CD, which includes Kelly’s renditions of the cut songs “There But for You Go I” and “From This Day On.” Also included is another number that was excised from the film, “Come to Me, Bend to Me,” sweetly sung by John Gustafsen, who dubbed for Jimmie Thompson. But this isn’t Brigadoon as we all know and love it. — G.A.

Studio Cast, 1957 (Columbia/Sony)

Studio Cast, 1957 (Columbia/Sony)  (4 / 5) Here is one of the best studio cast albums of the 1950s, conducted by the great Lehman Engel. The orchestral and choral work is excellent, and the cast is strong — especially the female leads. Shirley Jones is the embodiment of Fiona, but the most thrilling bit of casting is Susan Johnson as Meg; both of that colorful character’s great comic songs, “The Love of My Life” and “My Mother’s Weddin’ Day,” are here in their raunchy entirety, and Johnson’s delivery of Lerner’s witty lyrics is brassy and brilliant. As for the men, Jack Cassidy brings star power to the role of Tommy, but some listeners may feel that he doesn’t have quite the right sort of legit Broadway voice for these songs; and Frank Poretta as Charlie, although a fine tenor, arguably sounds too mature for this boyish part. — G.A.

(4 / 5) Here is one of the best studio cast albums of the 1950s, conducted by the great Lehman Engel. The orchestral and choral work is excellent, and the cast is strong — especially the female leads. Shirley Jones is the embodiment of Fiona, but the most thrilling bit of casting is Susan Johnson as Meg; both of that colorful character’s great comic songs, “The Love of My Life” and “My Mother’s Weddin’ Day,” are here in their raunchy entirety, and Johnson’s delivery of Lerner’s witty lyrics is brassy and brilliant. As for the men, Jack Cassidy brings star power to the role of Tommy, but some listeners may feel that he doesn’t have quite the right sort of legit Broadway voice for these songs; and Frank Poretta as Charlie, although a fine tenor, arguably sounds too mature for this boyish part. — G.A.

Television Cast, 1966 (Columbia Special Projects/Sony)

Television Cast, 1966 (Columbia Special Projects/Sony)  (2 / 5) This recording contains only nine songs from the Brigadoon score, eliminating both of Meg Brockie’s songs as well as the opening chorus (“Once in the Highlands”), “Jeannie’s Packin’ Up,” “The Chase” sequence, the Wedding Dance, and the Sword Dance. The songs that were retained are presented on this album in some weird, random order, rather than as they appeared in the Broadway show and in the actual 1966 TV broadcast. Most of the keys have been significantly lowered from the originals, and the arrangements and orchestrations sound much more “pop” than “musical theater.” All of that makes this come across as more of an enjoyable, mid-’60s pop album of songs from Brigadoon than a cast recording, but the presence of Robert Goulet and Sally Ann Howes in the roles of Tommy and Fiona does give it some theater cred. Both sound glorious here, even in the lower keys, and someone named Tommy Carlisle does a lovely job with Charlie Dalrymple’s “I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and “Come to Me, Bend to Me.” Marlyn Mason delivers Meg Brockie’s few sung lines in “McConnachy Square” with enough charisma that it’s a shame she wasn’t given a shot at “The Love of My Life” and “My Mother’s Weddin’ Day.” [Note: This recording as originally released on LP had such a brief running time that it was later combined with the cast album of the 1968 TV version of Kiss Me, Kate, in which Goulet also starred, for Sony’s single-disc CD release.] — Michael Portantiere

(2 / 5) This recording contains only nine songs from the Brigadoon score, eliminating both of Meg Brockie’s songs as well as the opening chorus (“Once in the Highlands”), “Jeannie’s Packin’ Up,” “The Chase” sequence, the Wedding Dance, and the Sword Dance. The songs that were retained are presented on this album in some weird, random order, rather than as they appeared in the Broadway show and in the actual 1966 TV broadcast. Most of the keys have been significantly lowered from the originals, and the arrangements and orchestrations sound much more “pop” than “musical theater.” All of that makes this come across as more of an enjoyable, mid-’60s pop album of songs from Brigadoon than a cast recording, but the presence of Robert Goulet and Sally Ann Howes in the roles of Tommy and Fiona does give it some theater cred. Both sound glorious here, even in the lower keys, and someone named Tommy Carlisle does a lovely job with Charlie Dalrymple’s “I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and “Come to Me, Bend to Me.” Marlyn Mason delivers Meg Brockie’s few sung lines in “McConnachy Square” with enough charisma that it’s a shame she wasn’t given a shot at “The Love of My Life” and “My Mother’s Weddin’ Day.” [Note: This recording as originally released on LP had such a brief running time that it was later combined with the cast album of the 1968 TV version of Kiss Me, Kate, in which Goulet also starred, for Sony’s single-disc CD release.] — Michael Portantiere

Studio Cast, 1992 (Angel)

Studio Cast, 1992 (Angel)  (4 / 5) If you’re looking for an excellent, complete recording of Brigadoon in modern digital sound, here it is. The London Sinfonietta lovingly performs every bar of the score, and the cast is top-notch. Conductor John McGlinn presents the songs in a most lyrical, lush setting, achieving the perfection of a fine classical music recording. As Tommy, Brent Barrett sounds gorgeous. Rebecca Luker is just as well cast; she glides through Fiona’s numbers blissfully, her standout performance being “Waitin’ for My Dearie.” John Mark Ainsley is first-rate as Charlie in “I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and “Come to Me, Bend to Me,” and Judy Kaye is a terrific Meg, giving her character’s comic turns just the right amount of sass. Most of the ensemble work is excellent, although some of the chorus members sound a bit too operatic in their solo lines, and McGlinn’s conducting is impeccable. — G.A.

(4 / 5) If you’re looking for an excellent, complete recording of Brigadoon in modern digital sound, here it is. The London Sinfonietta lovingly performs every bar of the score, and the cast is top-notch. Conductor John McGlinn presents the songs in a most lyrical, lush setting, achieving the perfection of a fine classical music recording. As Tommy, Brent Barrett sounds gorgeous. Rebecca Luker is just as well cast; she glides through Fiona’s numbers blissfully, her standout performance being “Waitin’ for My Dearie.” John Mark Ainsley is first-rate as Charlie in “I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and “Come to Me, Bend to Me,” and Judy Kaye is a terrific Meg, giving her character’s comic turns just the right amount of sass. Most of the ensemble work is excellent, although some of the chorus members sound a bit too operatic in their solo lines, and McGlinn’s conducting is impeccable. — G.A.

Studio Cast, 1999 (JAY)

Studio Cast, 1999 (JAY)  (3 / 5) While many of the JAY company’s studio recordings of classic musicals are note-complete presentations of the respective scores, this album is a more traditional compilation of the songs from Brigadoon, for the most part eschewing the show’s dance music, scene transitions, etc. — although the extended dance section of “I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and the entr’acte are both included. Interestingly, this recording employs the character surnames that were swapped in for the original London production of Brigadoon in order to comport with authentic Scottish clan names. (Apparently, Alan Jay Lerner had failed to do his research in this regard, just as he had not studied British speech well enough to avoid using some American English phrases in his lyrics for My Fair Lady.) Thus, the MacLarens are here the MacKeiths, Charlie Dalrymple is Charlie Cameron, and so on. But since the only surnames sung in the lyrics are “Harry Beaton” (now “Harry Ritchie”) and the list of names in “My Mother’s Wedding Day,” this change is mostly evident from reading the cast of characters list in the notes for the album. Yet another anomaly: While George Dvorsky sings the leading male role of Tommy Albright on the edition of the recording that was distributed in the U.S., Ethan Freeman is heard on the version that was issued in the U.K. and elsewhere in Europe. Dvorsky does a lovely job with Tommy’s songs in the fine, authentically Scottish-sounding company of Janis Kelly as Fiona, Megan Kelly as Meg, and Maurice Clarke as Charlie. Though some of conductor Martin Yates’ tempo choices are very odd — the choral prologue is lethargically slow, “The Chase” is really too fast, etc. — the National Symphony Orchestra sounds great in a reverberant acoustic. — M.P.

(3 / 5) While many of the JAY company’s studio recordings of classic musicals are note-complete presentations of the respective scores, this album is a more traditional compilation of the songs from Brigadoon, for the most part eschewing the show’s dance music, scene transitions, etc. — although the extended dance section of “I’ll Go Home With Bonnie Jean” and the entr’acte are both included. Interestingly, this recording employs the character surnames that were swapped in for the original London production of Brigadoon in order to comport with authentic Scottish clan names. (Apparently, Alan Jay Lerner had failed to do his research in this regard, just as he had not studied British speech well enough to avoid using some American English phrases in his lyrics for My Fair Lady.) Thus, the MacLarens are here the MacKeiths, Charlie Dalrymple is Charlie Cameron, and so on. But since the only surnames sung in the lyrics are “Harry Beaton” (now “Harry Ritchie”) and the list of names in “My Mother’s Wedding Day,” this change is mostly evident from reading the cast of characters list in the notes for the album. Yet another anomaly: While George Dvorsky sings the leading male role of Tommy Albright on the edition of the recording that was distributed in the U.S., Ethan Freeman is heard on the version that was issued in the U.K. and elsewhere in Europe. Dvorsky does a lovely job with Tommy’s songs in the fine, authentically Scottish-sounding company of Janis Kelly as Fiona, Megan Kelly as Meg, and Maurice Clarke as Charlie. Though some of conductor Martin Yates’ tempo choices are very odd — the choral prologue is lethargically slow, “The Chase” is really too fast, etc. — the National Symphony Orchestra sounds great in a reverberant acoustic. — M.P.

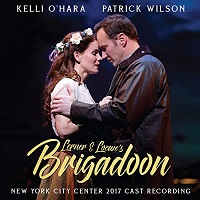

Encores! Cast, 2018 (Ghostlight)

Encores! Cast, 2018 (Ghostlight)  (4 / 5) Here’s a valuable aural document of one of the most moving and thrilling staged concert presentations of Brigadoon that one could ever hope to see. Kelli O’Hara and Patrick Wilson are sheer perfection in the leads; with her lush soprano, superb acting ability, and organic-sounding Scottish accent, O’Hara is a Fiona for the ages, while Wilson’s gorgeous, ringing baritenor and wonderfully natural way with spoken dialogue make him the ideal Tommy. Stephanie Block is spot-on luxury casting as Meg, and Ross Lekites sings Charlie’s songs with a melting beauty to rival the best of his recorded predecessors. Rob Berman conducts the large orchestra with a marvelously theatrical sense of forward motion, and the ensemble is exceptionally strong, whether its members are singing as a group or persuasively delivering solo lines in such songs as “Down on MacConnachy Square,” “Waitin’ for My Dearie,” and “The Chase.” Some listeners will miss the opening chorale “Once in the highlands….” and the charming if rather twee “Jeannie’s Packin’ Up,” both cut from the production and not heard here, plus there are some other minor excisions and revisions to the score that may bother purists. Still, overall, this is a treasurable cast album of a production as miraculous as the town of Brigadoon itself. — M.P.

(4 / 5) Here’s a valuable aural document of one of the most moving and thrilling staged concert presentations of Brigadoon that one could ever hope to see. Kelli O’Hara and Patrick Wilson are sheer perfection in the leads; with her lush soprano, superb acting ability, and organic-sounding Scottish accent, O’Hara is a Fiona for the ages, while Wilson’s gorgeous, ringing baritenor and wonderfully natural way with spoken dialogue make him the ideal Tommy. Stephanie Block is spot-on luxury casting as Meg, and Ross Lekites sings Charlie’s songs with a melting beauty to rival the best of his recorded predecessors. Rob Berman conducts the large orchestra with a marvelously theatrical sense of forward motion, and the ensemble is exceptionally strong, whether its members are singing as a group or persuasively delivering solo lines in such songs as “Down on MacConnachy Square,” “Waitin’ for My Dearie,” and “The Chase.” Some listeners will miss the opening chorale “Once in the highlands….” and the charming if rather twee “Jeannie’s Packin’ Up,” both cut from the production and not heard here, plus there are some other minor excisions and revisions to the score that may bother purists. Still, overall, this is a treasurable cast album of a production as miraculous as the town of Brigadoon itself. — M.P.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

“World Premiere Cast Recording,” 2000 (Original Cast Records, 2CDs)

“World Premiere Cast Recording,” 2000 (Original Cast Records, 2CDs)  (4 / 5) This is possibly the strangest cast album ever. The show Breakfast at Tiffany’s was a notorious flop of the 1960s, undergoing tryout traumas and then flaming out after a couple of New York previews. Nobody involved knew how to adapt Truman Capote’s novella about the adventures of winsome Holly Golightly, and Philadelphia audiences expecting the fey charm of the film version (which starred Audrey Hepburn) instead got a leering sex comedy by Abe Burrows with brassy songs by Bob Merrill. In an act of desperation, producer David Merrick replaced Burrows with Edward Albee, whose weird new concept — Holly as a fictional character romancing the writer who invents her — was quickly dismissed. As the changes kept coming, Merrill kept churning out songs. This two-disc studio album, actually recorded in 1995, has 33 tracks, including the overture, entr’acte, and exit music. The notes provide synopses of both Burrows’ and Albee’s libretti, allowing you to program different versions of the score when you listen. (There are also several alternate numbers that were written on the road.) It’s a pity that all this effort wasn’t expended on a better show. The Burrows version has its moments, but even so, Holly is stripped of her charm and made into a pushy gold digger. The Albee version isn’t as crass, but is humorless, with much weaker songs. There are a few nice items, including the swingy “Holly Golightly” and “Traveling.” But too many numbers, such as “Lament for Ten Men,” “The Home for Wayward Girls,” and “The Wittiest Fellow in Pittsburgh,” are simply tasteless. (Ralph Burns’ orchestrations underline every joke, in case you’re not paying attention.) The cast features Faith Prince singing her heart out as Holly, with strong contributions by John Schneider as the writer who loves her; Hal Linden as her hayseed first husband; Ron Raines as her Mafia confidant; and, from the Broadway cast, Sally Kellerman as Holly’s friendly competitor, whose big solo, “My Nice Ways,” has a certain dirty allure. Hardcore show fans will want to give this recording a listen at least once, but don’t expect a lost masterpiece. — David Barbour

(4 / 5) This is possibly the strangest cast album ever. The show Breakfast at Tiffany’s was a notorious flop of the 1960s, undergoing tryout traumas and then flaming out after a couple of New York previews. Nobody involved knew how to adapt Truman Capote’s novella about the adventures of winsome Holly Golightly, and Philadelphia audiences expecting the fey charm of the film version (which starred Audrey Hepburn) instead got a leering sex comedy by Abe Burrows with brassy songs by Bob Merrill. In an act of desperation, producer David Merrick replaced Burrows with Edward Albee, whose weird new concept — Holly as a fictional character romancing the writer who invents her — was quickly dismissed. As the changes kept coming, Merrill kept churning out songs. This two-disc studio album, actually recorded in 1995, has 33 tracks, including the overture, entr’acte, and exit music. The notes provide synopses of both Burrows’ and Albee’s libretti, allowing you to program different versions of the score when you listen. (There are also several alternate numbers that were written on the road.) It’s a pity that all this effort wasn’t expended on a better show. The Burrows version has its moments, but even so, Holly is stripped of her charm and made into a pushy gold digger. The Albee version isn’t as crass, but is humorless, with much weaker songs. There are a few nice items, including the swingy “Holly Golightly” and “Traveling.” But too many numbers, such as “Lament for Ten Men,” “The Home for Wayward Girls,” and “The Wittiest Fellow in Pittsburgh,” are simply tasteless. (Ralph Burns’ orchestrations underline every joke, in case you’re not paying attention.) The cast features Faith Prince singing her heart out as Holly, with strong contributions by John Schneider as the writer who loves her; Hal Linden as her hayseed first husband; Ron Raines as her Mafia confidant; and, from the Broadway cast, Sally Kellerman as Holly’s friendly competitor, whose big solo, “My Nice Ways,” has a certain dirty allure. Hardcore show fans will want to give this recording a listen at least once, but don’t expect a lost masterpiece. — David Barbour

Bravo Giovanni

Original Broadway Cast, 1962 (Columbia/DRG)

Original Broadway Cast, 1962 (Columbia/DRG)  (3 / 5) This is a swell listen with a game cast, a lively Ronny Graham-Milton Schafer score, and the sort of floppola production numbers that are more fun than higher-reaching material in worthier musicals. A contrived tale of dueling restaurateurs in Rome, Bravo Giovanni also takes in a May-September romance (September didn’t look too bad in the person of Metropolitan Opera basso Cesare Siepi), a young Michele Lee belting “Steady, Steady” and other power ballads with intensity, and a manic Maria Karnilova flogging something called “The Kangaroo.” Siepi is strong and authoritative, especially in the winning “If I Were the Man,” and such sundry talents as George S. Irving and David Opatoshu work hard selling their substandard songs. There’s even a hit faux-Italiano ballad, “Ah! Camminare,” delivered by the reliable Broadway tenor Gene Varrone. The CD reissue has a bonus-track enticement: Lee in a rock-beat version of “Steady, Steady,” Like the show itself, it’s cheesy fun. — Marc Miller

(3 / 5) This is a swell listen with a game cast, a lively Ronny Graham-Milton Schafer score, and the sort of floppola production numbers that are more fun than higher-reaching material in worthier musicals. A contrived tale of dueling restaurateurs in Rome, Bravo Giovanni also takes in a May-September romance (September didn’t look too bad in the person of Metropolitan Opera basso Cesare Siepi), a young Michele Lee belting “Steady, Steady” and other power ballads with intensity, and a manic Maria Karnilova flogging something called “The Kangaroo.” Siepi is strong and authoritative, especially in the winning “If I Were the Man,” and such sundry talents as George S. Irving and David Opatoshu work hard selling their substandard songs. There’s even a hit faux-Italiano ballad, “Ah! Camminare,” delivered by the reliable Broadway tenor Gene Varrone. The CD reissue has a bonus-track enticement: Lee in a rock-beat version of “Steady, Steady,” Like the show itself, it’s cheesy fun. — Marc Miller

The Boys From Syracuse

Studio Cast, 1953 (Columbia/Sony)

Studio Cast, 1953 (Columbia/Sony)  (3 / 5) Rodgers and Hart’s 1938 adaptation of The Comedy of Errors is one of their most sublime achievements. The score, melodically and harmonically unsurpassed and lyrically ingenious, has ensured frequent revivals of the show, so it’s no surprise that there are several recordings. The first, an early entry in Lehman Engel’s series of then-unrecorded musicals, is well cast and gratifyingly near complete; it even includes the entire Act II ballet. Casting Jack Cassidy as both Antipholuses (Antipholi?) is a little less fun than hiring two actors, but he’s at his vocal peak and is a persuasively sensuous balladeer; when Cassidy sings “You Have Cast Your Shadow on the Sea,” you know he’s not talking about refracted light. Portia Nelson delivers the goods in”Falling in Love With Love,” Bibi Osterwald as Luce lands all of her comic songs, and Engel conducts at a good clip. The orchestrations aren’t quite the Hans Spialek originals, but are modeled upon them. (The one exception is a bizarre, jazz-combo-backed version of “This Can’t Be Love” that Rodgers himself went on record as loathing.) Some of Columbia’s subsequent studio cast albums were mired in star casting and ’50s orchestral bloat; this one is closer to the real thing, with the correct spirit of silliness and a knockout of an overture. — Marc Miller

(3 / 5) Rodgers and Hart’s 1938 adaptation of The Comedy of Errors is one of their most sublime achievements. The score, melodically and harmonically unsurpassed and lyrically ingenious, has ensured frequent revivals of the show, so it’s no surprise that there are several recordings. The first, an early entry in Lehman Engel’s series of then-unrecorded musicals, is well cast and gratifyingly near complete; it even includes the entire Act II ballet. Casting Jack Cassidy as both Antipholuses (Antipholi?) is a little less fun than hiring two actors, but he’s at his vocal peak and is a persuasively sensuous balladeer; when Cassidy sings “You Have Cast Your Shadow on the Sea,” you know he’s not talking about refracted light. Portia Nelson delivers the goods in”Falling in Love With Love,” Bibi Osterwald as Luce lands all of her comic songs, and Engel conducts at a good clip. The orchestrations aren’t quite the Hans Spialek originals, but are modeled upon them. (The one exception is a bizarre, jazz-combo-backed version of “This Can’t Be Love” that Rodgers himself went on record as loathing.) Some of Columbia’s subsequent studio cast albums were mired in star casting and ’50s orchestral bloat; this one is closer to the real thing, with the correct spirit of silliness and a knockout of an overture. — Marc Miller

Off-Broadway Cast, 1963 (Capitol/Angel)

Off-Broadway Cast, 1963 (Capitol/Angel)  (4 / 5) The orchestrations here are scaled-down approximations of the original Spialek charts; by Off-Broadway standards, the orchestra is quite large. The cover art features that great Al Hirschfeld drawing of Jimmy Savo and Teddy Hart in the 1938 original, and what’s on the recording is pretty delectable, too. Karen Morrow’s brazen voice richly mines the comedy songs, Clifford David and Stuart Damon split the ballads ably, and Ellen Hanley breaks your heart with “Falling in Love With Love.” Also on hand are Danny Carroll, Julienne Marie, and Cathryn Damon. The Encores! album (reviewed below) may be the gold-standard recording of this score, but this one is more persuasively about hot-blooded young folks jumping into the wrong beds. — M.M.

(4 / 5) The orchestrations here are scaled-down approximations of the original Spialek charts; by Off-Broadway standards, the orchestra is quite large. The cover art features that great Al Hirschfeld drawing of Jimmy Savo and Teddy Hart in the 1938 original, and what’s on the recording is pretty delectable, too. Karen Morrow’s brazen voice richly mines the comedy songs, Clifford David and Stuart Damon split the ballads ably, and Ellen Hanley breaks your heart with “Falling in Love With Love.” Also on hand are Danny Carroll, Julienne Marie, and Cathryn Damon. The Encores! album (reviewed below) may be the gold-standard recording of this score, but this one is more persuasively about hot-blooded young folks jumping into the wrong beds. — M.M.

Original London Cast, 1963 (Decca)

Original London Cast, 1963 (Decca)  (3 / 5) Apparently, when The Boys From Syracuse made its belated London debut, the elements didn’t quite jell; a three-month run was all that the show could muster in the West End. But the album has good ensemble work from a big-name British cast headed by Bob Monkhouse, Denis Quilley, and Maggie Fitzgibbon. The production is a bit boisterous; all that hearty chorus laughter at Hart’s jokes tells us that the director (Christopher Hewett) didn’t trust the audience to identify the funny bits. Still, this is an above-average recording of a fabulous score. The CD reissue booklet boasts an excellent essay on the show, including a scholarly mini-course in Rodgers and Hart appreciation by John Hollander. Six vintage tracks by Frances Langford and Rudy Vallee are included on the disc as bonuses, but they’re soporific. — M.M.

(3 / 5) Apparently, when The Boys From Syracuse made its belated London debut, the elements didn’t quite jell; a three-month run was all that the show could muster in the West End. But the album has good ensemble work from a big-name British cast headed by Bob Monkhouse, Denis Quilley, and Maggie Fitzgibbon. The production is a bit boisterous; all that hearty chorus laughter at Hart’s jokes tells us that the director (Christopher Hewett) didn’t trust the audience to identify the funny bits. Still, this is an above-average recording of a fabulous score. The CD reissue booklet boasts an excellent essay on the show, including a scholarly mini-course in Rodgers and Hart appreciation by John Hollander. Six vintage tracks by Frances Langford and Rudy Vallee are included on the disc as bonuses, but they’re soporific. — M.M.

Encores! Cast, 1997 (DRG)

Encores! Cast, 1997 (DRG)  (5 / 5) A treat under any circumstances, the score of The Boys From Syracuse never sounded better than in this recording of the City Center Encores! production. First and foremost, it restores Hans Spialek’s original orchestrations, and that alone is like scraping several coats of paint off an antique that never should have been tampered with. Exquisite details emerge, like the orchestra tacet in “This Can’t Be Love” when Sarah Uriarte Berry sings that her heart “skipped a beat.” Also, this is the most complete rendition of the score on record, featuring the seldom-heard “Big Brother” and the premiere recording of “Let Antipholus In!” The casting, while not uniformly inspired, is perfectly sensible. If Debbie Gravitte as Luce never produces an unexpected inflection, she does the job, and she’s well partnered by Michael McGrath as Dromio of Ephesus; their mutual disgust in “What Can You Do With a Man?” is palpable. The strong Antipholuses are Davis Gaines and Malcom Gets. Rebecca Luker as Adriana is all that you want her to be, and Patrick Quinn injects mock-Romberg testosterone into “Come With Me.” But it’s McGrath who taps directly into the show’s spirit, as when he delivers one of my favorite Hart couplets: “Come on, crystal, act like ya know me / Come on, crystal, show me Dromie!” — M.M.

(5 / 5) A treat under any circumstances, the score of The Boys From Syracuse never sounded better than in this recording of the City Center Encores! production. First and foremost, it restores Hans Spialek’s original orchestrations, and that alone is like scraping several coats of paint off an antique that never should have been tampered with. Exquisite details emerge, like the orchestra tacet in “This Can’t Be Love” when Sarah Uriarte Berry sings that her heart “skipped a beat.” Also, this is the most complete rendition of the score on record, featuring the seldom-heard “Big Brother” and the premiere recording of “Let Antipholus In!” The casting, while not uniformly inspired, is perfectly sensible. If Debbie Gravitte as Luce never produces an unexpected inflection, she does the job, and she’s well partnered by Michael McGrath as Dromio of Ephesus; their mutual disgust in “What Can You Do With a Man?” is palpable. The strong Antipholuses are Davis Gaines and Malcom Gets. Rebecca Luker as Adriana is all that you want her to be, and Patrick Quinn injects mock-Romberg testosterone into “Come With Me.” But it’s McGrath who taps directly into the show’s spirit, as when he delivers one of my favorite Hart couplets: “Come on, crystal, act like ya know me / Come on, crystal, show me Dromie!” — M.M.

Boy Meets Boy

Original Off-Broadway Cast, 1974 (Records & Publishing/AEI)

Original Off-Broadway Cast, 1974 (Records & Publishing/AEI)  (2 / 5) This show dates from the mid ’70s, but its heart lies more with The Boy Friend than with The Boys in the Band. The creators took one of those cheerfully asinine 1930s musical comedy plots (globe-trotting reporter meets incognito aristocrat) and gave it a gay spin. There’s no post-Stonewall anger here, no Suddenly, Last Summer angst and self-loathing; this show is a fizzy, good-hearted romp. The missing ingredient is a true sense of style. Composer-lyricist Bill Solly came up with some competent wordplay and nice melodies, but the score is more ’70s-generic than ’30s satiny chic. That problem is exacerbated on this recording by the tinny noises of synthesized accompaniment. Still, the small cast performs enthusiastically, and if the result is not a masterful confection, it is a tasty cupcake at the very least. From today’s perspective, Boy Meets Boy seems a period piece twice over, a giddy bauble that appeared just before a very dark time in gay history began. Even nostalgia can wield a double-edged sword. — Richard Barrios

(2 / 5) This show dates from the mid ’70s, but its heart lies more with The Boy Friend than with The Boys in the Band. The creators took one of those cheerfully asinine 1930s musical comedy plots (globe-trotting reporter meets incognito aristocrat) and gave it a gay spin. There’s no post-Stonewall anger here, no Suddenly, Last Summer angst and self-loathing; this show is a fizzy, good-hearted romp. The missing ingredient is a true sense of style. Composer-lyricist Bill Solly came up with some competent wordplay and nice melodies, but the score is more ’70s-generic than ’30s satiny chic. That problem is exacerbated on this recording by the tinny noises of synthesized accompaniment. Still, the small cast performs enthusiastically, and if the result is not a masterful confection, it is a tasty cupcake at the very least. From today’s perspective, Boy Meets Boy seems a period piece twice over, a giddy bauble that appeared just before a very dark time in gay history began. Even nostalgia can wield a double-edged sword. — Richard Barrios

Original Minneapolis Cast, 1979 (Private Editions/no CD)

Original Minneapolis Cast, 1979 (Private Editions/no CD)  (3 / 5) Boy Meets Boy was sufficiently successful in its initial New York and Los Angeles runs to become a hot item on the burgeoning gay-regional-theater circuit of the late 1970s. (Some playgoers will recall those halcyon days of generous grants from the National Endowment for the Arts.) One company in particular, the Out & About Theatre of Minneapolis, gave Bill Solly’s show a comparatively lavish production. A special boon for the home listener is that the cast album boasts a small but bona-fide orchestra to supplant the nattering synthesizer heard on the original recording; the intrepid orchestrator Brad Callahan worked with Solly to expand the score somewhat, and the added resources give the show more of a faux-Deco sheen. A new overture, extended dance music, and an ingratiating group of performers add to the fun. Calling something “the Original Minneapolis Cast Recording” may sound as camp as anything in the show itself, but this album demonstrates how a good budget and a thoughtful presentation can benefit a little musical. —R.B.

(3 / 5) Boy Meets Boy was sufficiently successful in its initial New York and Los Angeles runs to become a hot item on the burgeoning gay-regional-theater circuit of the late 1970s. (Some playgoers will recall those halcyon days of generous grants from the National Endowment for the Arts.) One company in particular, the Out & About Theatre of Minneapolis, gave Bill Solly’s show a comparatively lavish production. A special boon for the home listener is that the cast album boasts a small but bona-fide orchestra to supplant the nattering synthesizer heard on the original recording; the intrepid orchestrator Brad Callahan worked with Solly to expand the score somewhat, and the added resources give the show more of a faux-Deco sheen. A new overture, extended dance music, and an ingratiating group of performers add to the fun. Calling something “the Original Minneapolis Cast Recording” may sound as camp as anything in the show itself, but this album demonstrates how a good budget and a thoughtful presentation can benefit a little musical. —R.B.

The Boy Friend

Original London Cast, 1954 (HMV/Sepia)

Original London Cast, 1954 (HMV/Sepia)  (3 / 5) A pastiche of 1920s tuners with an absurd but dear book and a Sandy Wilson score packed with wonderful tunes, The Boy Friend is presented here in a cast album of the show’s first full production. As such, this is the most “authentic” of the musical’s various recordings, but others are more complete, more fully orchestrated, and boast better singers. Many of the songs were edited down for this recording, and “Safety in Numbers” and “The ‘You-Don’t-Want-to-Play-With-Me’ Blues” are missing entirely. The performers set the tone for those who followed. Anne Rogers is Polly, the finishing-school student who falls in love with a messenger who turns out to be the son of a lord; Denise Hurst is Maisie, in love with wealthy Bobby Van Dusen; and Maria Charles is Dulcie, who has a flirtation with Lord Brockhurst. The plot comes to what is described as an ending “in which everybody is successfully paired off in a matter of minutes.” — David Wolf

(3 / 5) A pastiche of 1920s tuners with an absurd but dear book and a Sandy Wilson score packed with wonderful tunes, The Boy Friend is presented here in a cast album of the show’s first full production. As such, this is the most “authentic” of the musical’s various recordings, but others are more complete, more fully orchestrated, and boast better singers. Many of the songs were edited down for this recording, and “Safety in Numbers” and “The ‘You-Don’t-Want-to-Play-With-Me’ Blues” are missing entirely. The performers set the tone for those who followed. Anne Rogers is Polly, the finishing-school student who falls in love with a messenger who turns out to be the son of a lord; Denise Hurst is Maisie, in love with wealthy Bobby Van Dusen; and Maria Charles is Dulcie, who has a flirtation with Lord Brockhurst. The plot comes to what is described as an ending “in which everybody is successfully paired off in a matter of minutes.” — David Wolf

Original Broadway Cast, 1954 (RCA)

Original Broadway Cast, 1954 (RCA)  (4 / 5) When top-flight Broadway producers Cy Feuer and Ernest Martin got the American rights to The Boy Friend, they agreed to bring author Sandy Wilson and director Vida Hope to New York to ensure that the U.S. edition would be faithful to the London original. But the plan soon soured. According to Feuer’s autobiography, Wilson and Hope insisted on adding a new scene and song, which the producers vetoed. Wilson’s version of the story is that Feuer and Martin cut a song, switched actors from one role to another, and fired others. He claims they even tried to get rid of star Julie Andrews, whereas Feuer writes that he knew she was a genius all along. From all reports, the New York production was faster, louder, and broader than the original. In the only change that Wilson approved, the music was re-orchestrated (by Ted Royal and Charles L. Cooke), and more musicians were added. The Broadway cast performs with punch and precision, and the score sounds great on this recording — especially the snazzy new overture, which rides to a dazzling conclusion. — D.W.

(4 / 5) When top-flight Broadway producers Cy Feuer and Ernest Martin got the American rights to The Boy Friend, they agreed to bring author Sandy Wilson and director Vida Hope to New York to ensure that the U.S. edition would be faithful to the London original. But the plan soon soured. According to Feuer’s autobiography, Wilson and Hope insisted on adding a new scene and song, which the producers vetoed. Wilson’s version of the story is that Feuer and Martin cut a song, switched actors from one role to another, and fired others. He claims they even tried to get rid of star Julie Andrews, whereas Feuer writes that he knew she was a genius all along. From all reports, the New York production was faster, louder, and broader than the original. In the only change that Wilson approved, the music was re-orchestrated (by Ted Royal and Charles L. Cooke), and more musicians were added. The Broadway cast performs with punch and precision, and the score sounds great on this recording — especially the snazzy new overture, which rides to a dazzling conclusion. — D.W.

Broadway Revival Cast, 1970 (Decca)

Broadway Revival Cast, 1970 (Decca)  (4 / 5) The original Broadway production of The Boy Friend ran 485 performances, beginning in 1954. Three years later, the show was revived Off-Broadway and ran nearly twice as long. In 1970, it was revived again, this time on Broadway, and although the run was short, that production yielded a cast album that includes the Act II finale and other previously unrecorded numbers. Judy Carne, then a star of TV’s Laugh-In, got above-the-title solo billing but proved uninteresting onstage; while she sings well enough as Polly, she can’t compare with Julie Andrews or Anne Rogers. People who remember this production always refer to it as “the Sandy Duncan Boy Friend.” Indeed, Duncan was adorable in the secondary role of Maisie and got all the reviews (with her charming partner, Harvey Evans), but on the recording, she has some trouble with “Safety in Numbers.” Leon Shaw as Percy Browne sings his part of “Fancy Forgetting” poorly; Barbara Andres as Hortense speaks “It’s Nicer in Nice” rather than sings it; and the orchestra performs without the glorious abandon of the players on the first Broadway album. — D.W.